From Streamlit to Flask: When and Why to Make the Jump

A practical guide to migrating from Streamlit to Flask, based on real experience with the CM Rentals project. Learn when Streamlit hits its limits, how to choose its successor and how to plan and execute a successful migration.

Introduction

Creating apps in Streamlit feels like a natural extension for data work in Python. You’ve got your dataframes and charts, possibly already visualized in Jupyter Notebook. You decide to share your work as a web app, fire up Streamlit and…everything is so smooth.

You’re still in your known realm, operating on data. One method call and your table is displayed. Two more lines and you have a filter or a clickable button.

It’s less than a few hours and you’ve built a fully-fledged app. Everything is great, very idyllic…until it isn’t. You start hitting a wall, you’re literally battling the framework, trying to squeeze out more than it’s meant to offer.

A fantasy scenario? Not necessarily. This can be a reality of developing Streamlit applications. But it doesn’t have to be a harsh reality. Streamlit can be a fantastic tool when you embrace its strengths, while being aware of its limitations.

So in this guide we will tackle the problem of Streamlit not being the best fit anymore. The line between when it’s shining and when it’s underperforming can be blurry, so we will cover the process from the very beginning until the end - a successful migration to another tool.

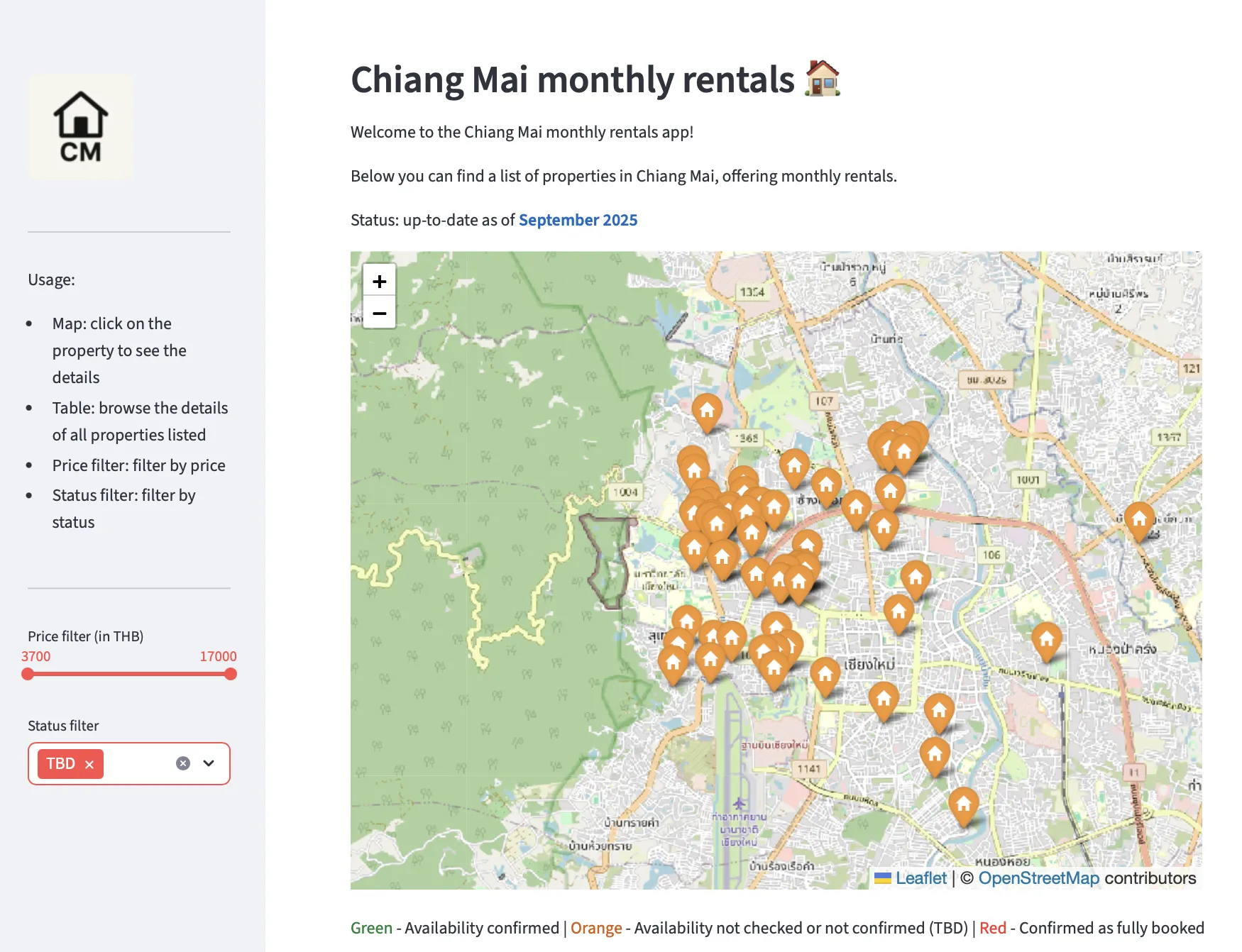

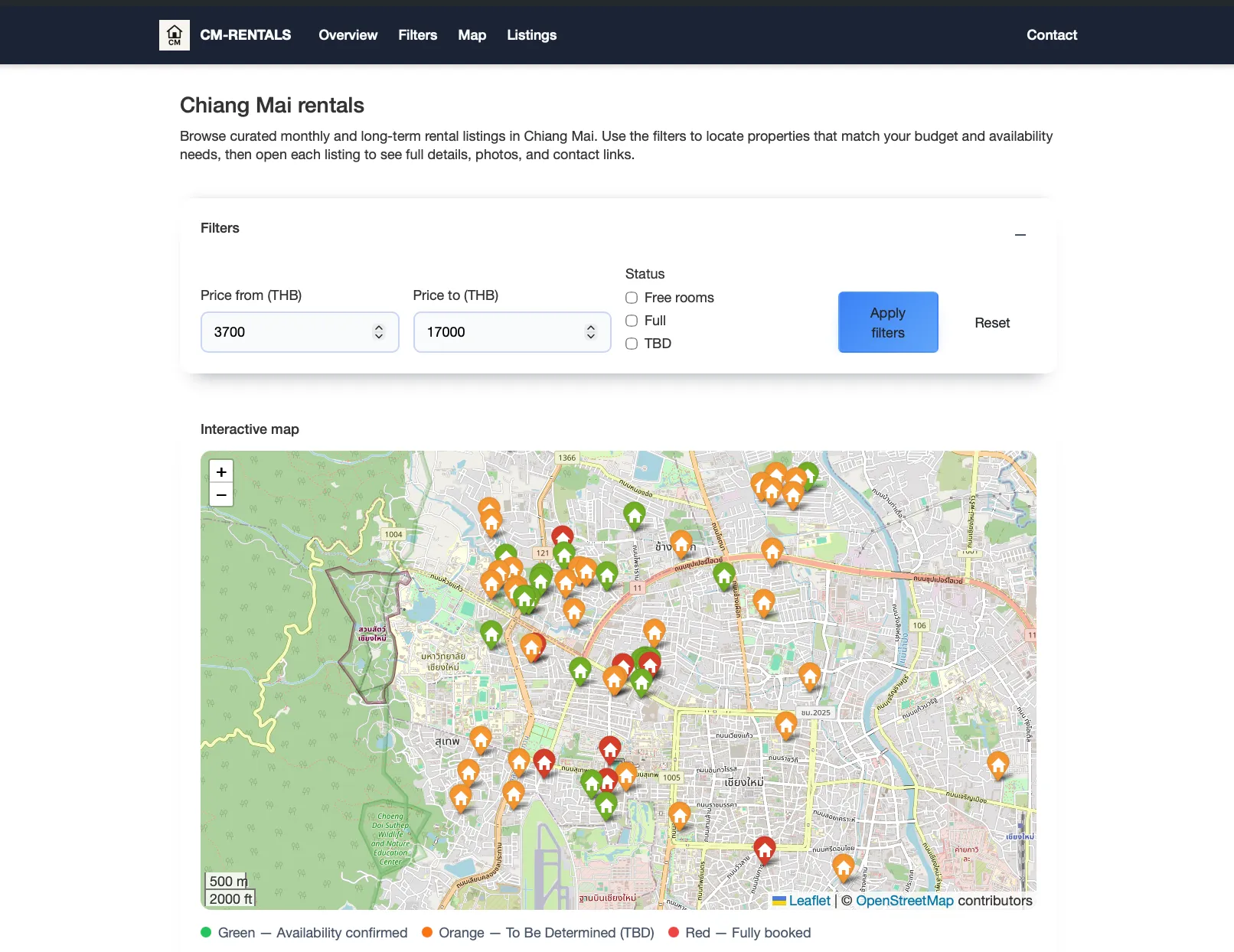

And we approach it from a practical perspective - I do have a couple of Streamlit applications under my belt, and with the last one, CM Rentals, I went through exactly this migration path to Flask.

What makes Streamlit unique

Traditional web development separates the backend (application logic) and frontend (user interface). Frontend means HTML, CSS, JavaScript, possibly React or Vue.js, while backend can involve even more languages and frameworks.

That’s potentially a lot of technologies. Meanwhile, in the data world, dashboards often weren’t enough - data professionals were expected to create web applications. But that meant a technology mismatch: frontend skills aren’t something data professionals typically have.

And that’s where Streamlit comes in clutch. It lets you build the entire app in one language - Python - abstracting away all the HTML, CSS and JavaScript complexity.

But the ease of development comes at the cost of many compromises, as we need some serious complexity under the hood to make it happen.

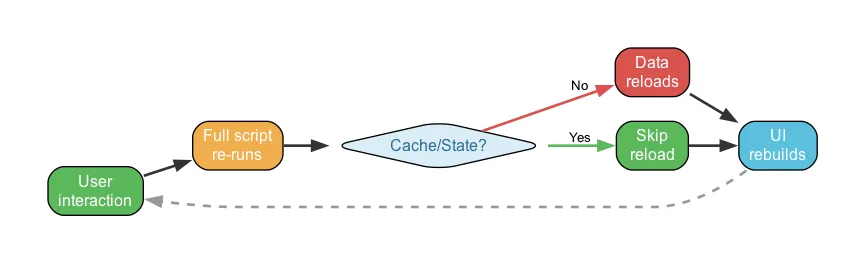

What we can achieve “traditionally” might not be possible in Streamlit at all, or will turn out to be overly complex. A crucial part of Streamlit is its reactivity - every interaction with the app, like clicking a button, means that the code for the whole app will be re-run. This introduces concepts of caching and session state management, which can quickly turn simple code into a real headache.

When Streamlit Works Great

Before diving into limitations, let’s acknowledge where Streamlit excels:

- Rapid prototyping - Get a working app in hours, with code you actually understand

- Data-focused applications - Built-in support for charts, tables, and data manipulation

- ML/AI demos - And the data focus extends to ML and AI, with built-in functions for features like chatbots

- Internal tools - All users get the link to the app directly, so you don’t need to worry about search engines or organic discovery

- Single-page applications - When you need one view with interactive widgets

- Utility first, appearance second - You focus on the app being functional, not on customizing the appearance

Signs You’ve Outgrown Streamlit

1. Maintaining Robust App State

Streamlit’s interactivity is a blessing and a curse at the same time. A full app re-run at every interaction means that:

- If you’re loading a table from a database, Streamlit will attempt to load it again anytime you click something in the app

- If you’re displaying a message after clicking a button and then you use another widget, like filter, the button message will disappear unless retained explicitly

Streamlit of course provides measures to prevent this and maintain the app state:

- Caching for saving the output of a function, meaning that effectively we can just load our dataset once

- Session state for retaining the state of the app, meaning that what we’ve clicked once is here to stay

And while caching might be a little bit easier to harness, session state might be a real hassle if we just want to retain too much.

2. Performance

Even if somehow we have managed to have immaculate caching and session state, Streamlit still needs to do very heavy lifting in the background to render our Python-only code with a local web server and the frontend.

So no matter how much optimization we implement in our code, Streamlit is still an extra abstraction layer, and a real performance boost might be possible only by…not using Streamlit.

3. SEO Limitations

Streamlit apps are essentially single-page applications rendered client-side. There’s limited control over meta tags, URLs, and page structure, so search engines struggle to index the content properly.

So if our app goes ‘public’, there’s a good chance it will struggle to climb to that #1 position in Google search.

4. Dynamic pages

Streamlit allows multipage apps, but it’s still a single-page application at its core.

For CM Rentals, we needed dynamic pages for:

- Functionality - dedicated pages for each property with all its information

- SEO - each page indexed separately by Google, directly discoverable

We wanted URLs like https://cm-rentals.com/listing/cosy-apartment - but this is effectively impossible in Streamlit, as each “page” must be declared explicitly.

However, in our case dynamic is the keyword - properties come from a database and change over time, so we can’t hardcode them. The app should generate URLs automatically.

The best Streamlit can do for dynamic content is hash-based sections like https://cmrentals.tojest.dev/#cosy-apartment - nowhere near what we needed.

5. Layout Constraints

Streamlit comes with a pre-designed layout. Fully functional and looks good out of the box. But if you want to go more custom, then it can be very cumbersome to make it your own.

6. Mobile capabilities

Streamlit has no built-in mobile features. External libraries can help retrieve screen size and such, so we can adjust the appearance at least a little bit. But it’s still far from perfect - the mobile experience won’t match desktop.

What’s next? The Migration Path

Identifying bottlenecks

The Streamlit app is working, it has received positive feedback, why would we change anything? That’s a very valid point, and if we consider the project as finished then we could just end it here.

But if we continue developing it, we need to identify what’s working and what’s not, weighing the costs:

- Staying with Streamlit - potentially struggling with (or preventing) app growth

- Migrating - extra time now, but potential time savings and smoother growth later

We got a functional app in no time. But going forward, the pain points were becoming clear:

- Dynamic pages - we needed dedicated pages for each property, impossible in Streamlit

- SEO - the app was public, and Streamlit doesn’t shine here

- Layout & mobile - the default Streamlit look wasn’t cutting it for a public-facing app

- Performance - visible loading times that would require compromising code simplicity to fix

We outgrew Streamlit in all the areas that matter for a public-facing web application. For an internal tool, most of these wouldn’t be concerns.

We were also outside data-centric app boundaries - just dozens of records, no heavy computation. Simply retrieve and display. So besides the functional layer, the importance of appearance was actually knocking here.

Redefining the requirements

Before exploring options, let’s reconsider our actual requirements.

Usage of Streamlit imposes some rules on us. It’s not only the functional and visual constraints, but also the reactivity. App reload after every interaction is actually the highest degree of interactivity possible. But do we need that much? The answer is - no, not at all.

Our requirements:

- Keep all features - map display, property table, filtering

- Retain the database schema - no point reorganizing a working data layer

- Keep external integrations - Supabase, Folium

- Add dedicated property pages - for SEO and UX

- Improve layout and mobile responsiveness

For reactivity:

- Load all data on page load

- Filters don’t need to be instant - clicking “Apply” button is perfectly acceptable

The conclusion: we don’t need a highly interactive application. A static website with pre-loaded content will do. This aligns with our SEO goals and should make the code simpler.

Choosing the new tech stack

So the decision is made - farewell Streamlit. But the abundance of web technologies can be staggering and intimidating at the same time.

Tech-stack prerequisites

We need constraints. Starting from our Python background:

- Stay with Python - leveraging what we know, not jumping to distinct (for us) technologies like PHP or .Net

- Accept learning some new technologies if needed

- Avoid frameworks with steep learning curves - our app isn’t that complex

Python-based data frameworks

Streamlit is actually not one of a kind. There are more tools boasting to be all-in-one, allowing to create web apps only with Python, focusing on data. Dash, Panel, NiceGUI, Reflex, the list can go on. Usually they will avoid this problematic full re-run, and will potentially offer bigger capabilities as well.

However, switching to another data framework is unlikely to solve our core problems. While some (like Dash) offer better URL routing, they still share fundamental constraints on SEO and layout control.

Full-stack frameworks

So we enter the full-stack world. And that world is really vast, with three main setups available:

- Separate Backend + Frontend - Most complex, most capable

- Backend + HTML templates - Server-Side Rendering (SSR), simpler if high interactivity isn’t needed

- Frontend + Backend-as-a-Service - JavaScript-heavy, highly interactive, relying on Client-Side Rendering (CSR)

Decision process

Our requirements narrow this down:

- Cross out Frontend + BaaS - doesn’t favour SEO, JavaScript-heavy, can’t leverage Python

- Cross out full separate stack - overengineering for our needs

That leaves Backend + Templates. Within Python:

- Flask - simplest, most lightweight

- Django - “batteries included”, great for larger projects, potentially too heavy here

- FastAPI - excellent for APIs, but server-rendered pages aren’t its strength

Flask was the natural choice - lightweight, flexible, and Jinja2 templates give us the server-side rendering we need for SEO.

Implementation plan

We have our winner. But how to proceed with the migration now?

-

Keep the Streamlit code as reference - do not erase it. Create a new git repository - having both codebases helps understand the Flask code by comparing it with the original.

-

Choose your coding approach. Write it yourself, or leverage AI - there’s never been a better time to say: “I have my app in technology X, please rewrite it in technology Y”

-

Create a Product Requirements Document (PRD). We already have our redefined requirements. Listing features, new additions, and layout expectations significantly decreases disappointment with the first version.

-

Iterate feature by feature. Work on one feature at a time, ensuring it works before moving on.

-

Test throughout. Don’t forget mobile testing - UX and mobile-friendliness are key aspects here.

Flask vs Streamlit - Core Differences

So what does it actually look like to go from Streamlit to Flask? The fundamental difference is that Flask separates what Streamlit combines.

In Streamlit, your Python code is your app - the logic, the layout, the interactivity, all in one place. In Flask, these concerns are split:

- Routes (Python) - define what happens when someone visits a URL

- Templates (HTML/Jinja2) - define what the page looks like

- Static files (CSS/JS) - handle styling and interactivity

This means more files and more structure, but also full control. Every HTML element, every CSS rule, every URL is yours to define.

To illustrate with a simple example:

Streamlit - display a property:

st.write(f"# {property.title}")

st.write(property.description)

col1, col2 = st.columns(2)

with col1:

st.metric("Price", f"${property.price}/month")Flask - the same thing, but separated into a route and a template:

Route (Python):

@app.route('/listing/<slug>')

def listing(slug):

property = get_property_by_slug(slug)

return render_template('listing.html', property=property)Template (HTML/Jinja2):

<h1>{{ property.title }}</h1>

<p>{{ property.description }}</p>

<div class="price">{{ property.price }}/month</div>More code? Yes. But notice what we got: a clean URL (/listing/cosy-apartment), full HTML control, and the ability to add meta tags, structured data, or any CSS we want. These are the things that weren’t possible in Streamlit.

For filtering? Standard HTML forms with a GET request do the job. Simple, reliable, no JavaScript framework required.

Streamlit’s built-in widgets are arguably easier to set up. But Flask gives you full control over how filters look, how URLs change, and how results display.

Project structures also differ - Flask has more folders and files, but both remain easy to follow:

Streamlit project structure:

cm-rentals-streamlit/

├── app.py # Main entry point - all UI code here

├── pg/

│ ├── form.py # Form page logic

│ └── map.py # Map page logic

├── property_map/

│ ├── db.py # Database queries

│ └── map_utils.py # Map utilities

├── static/

│ └── robots.txt

└── requirements.txtFlask project structure:

cm-rentals-flask/

├── flask_app/

│ ├── __init__.py # App factory

│ ├── config.py # Configuration

│ ├── constants.py # Constants

│ ├── errors.py # Error handlers

│ ├── views.py # Route definitions

│ ├── services/

│ │ └── properties.py # Business logic

│ └── utils/

│ └── map_builder.py # Map utilities

├── templates/ # HTML templates (Jinja2)

│ ├── base.html # Base layout

│ ├── index.html # Homepage

│ ├── listing_detail.html # Property page

│ ├── privacy.html

│ └── errors/

│ ├── 404.html

│ └── 500.html

├── static/

│ └── css/

│ └── main.css # Custom styles

├── wsgi.py # WSGI entry point

└── requirements.txtStreamlit: 5 Python files. Flask: 10 Python files plus 6 HTML templates and a CSS file. More files, but more control. With Flask we even have custom error pages - a “real web app” in every aspect.

Results

After the migration, the differences were clear:

| Metric | Streamlit | Flask |

|---|---|---|

| Time to usable content | ~3-4s | ~1.7s |

| Lighthouse Performance | Couldn’t measure* | 68** |

| Google indexed pages | 1 | 50+ |

| Mobile usability | Limited | Full |

| Layout control | Constrained | Complete |

*Lighthouse timed out waiting for Streamlit to render content (NO_FCP error). Streamlit’s HTML loads fast, but it’s an empty shell - users watch the “running man” spinner while JavaScript renders the actual content. Flask sends ready-to-display HTML.

**Flask’s 68 Lighthouse score isn’t very impressive - image optimization and other tweaks could push it higher. But for a side project, “measurable and indexable” was already a big step up from “couldn’t measure at all.”

The biggest win was SEO: going from one indexable page to over 50 individual property pages, each discoverable through Google search. If Google’s tools can’t measure your app, search engines will struggle to index it.

And the layout freedom - being able to design the pages exactly how I wanted, without fighting Streamlit’s constraints - was honestly a relief.

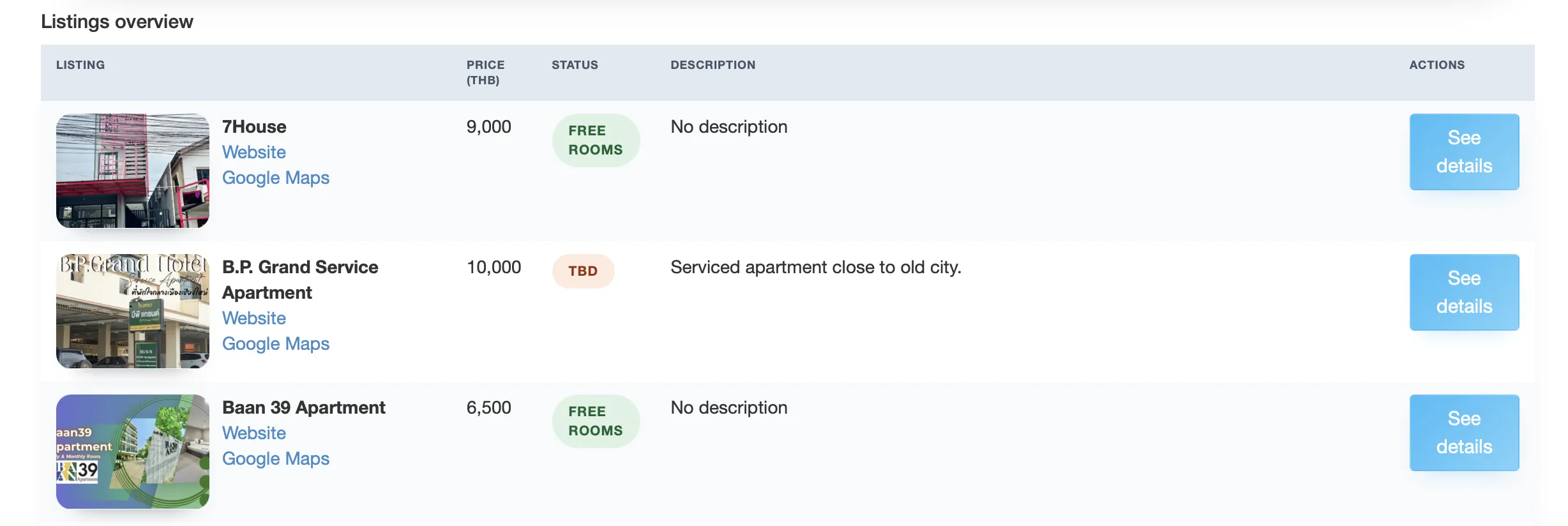

But does it actually look better?

The UI is much cleaner now, with traditional navigation headers making the site easy to browse.

The table is also much more appealing. We could have tried to make it more sophisticated in Streamlit as well, but it would require direct HTML - not straightforward.

Lessons Learned

1. Each project migration will be different

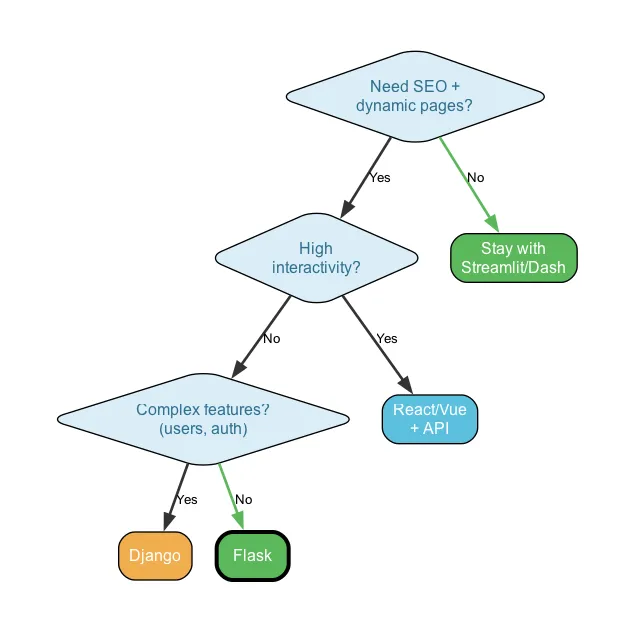

There’s no default rule that Streamlit-to-Flask migration is always the right choice.

We did a thorough assessment leading to Flask. Different projects with different goals might need React/Vue.js (for interactivity) or Django (for complex features like user accounts, comments, ratings).

So while our decision process was as follows, it might still vary heavily for other projects.

2. Don’t Over-Engineer

Web dev world is not only vast, but also very volatile, changing rapidly. There will always be some new frameworks, shiny tools and most popular choices. And that puts us at risk of going down a rabbit hole, choosing overly complicated tools and not leveraging our current skills.

3. Control the whole migration and development process

Even when delegating coding to AI, you must stay in the loop and understand your codebase.

Without clear requirements and the right AI tool (Claude Code in this case), we might have ended up with an over-engineered JavaScript framework. Instead, we made conscious choices from the beginning, maintaining control while leveraging LLMs for code creation.

4. Database is the backbone, no matter the technologies used for the app itself

Having a data background, we understand the importance of solid data foundations from the start. Outside data world, this often gets neglected, leading to serious issues in syncing the application itself and the database.

With the right approach, our data layer perfectly integrates with any technology. Streamlit or Flask - same database, same tables. Only the app code differs.

5. Streamlit Skills Transfer

Good news: you’re not starting from zero. Session management, caching, database queries - the mental models carry over, just implemented differently. Same Python ecosystem, same libraries.

And having wrestled with Streamlit’s session state? You’ll appreciate how other frameworks handle it (spoiler: much simpler).

When to Stay with Streamlit

Migration isn’t always the answer. Before committing to a rewrite, honestly assess if you actually need it. Stay with Streamlit if:

- Your app is internal-only - no SEO concerns, no public users

- Appearance is secondary - the default look is fine for your use case

- You need rapid iteration over polish - shipping fast matters more than pixel-perfect design

- Your team knows Python but not web development - and learning HTML/CSS/JS isn’t on the roadmap

- The app is data-exploration focused - exactly what Streamlit was built for

Nothing wrong with that. Sometimes Streamlit is exactly the right tool - acknowledging that is as important as knowing when to move on.

Conclusion

The CM Rentals migration was a significant effort. But the result - a faster, SEO-friendly, mobile-responsive application with complete design control - made it worth it.

The real takeaway isn’t “Flask is better than Streamlit.” It’s that Streamlit and Flask aren’t competitors - they’re tools for different stages and different needs. Start fast with Streamlit to validate your idea, and migrate when (and if) you outgrow it.

Facing a similar decision? Check out the CM Rentals project page to see the result, or reach out if you want to discuss specifics.